- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Policy and Law

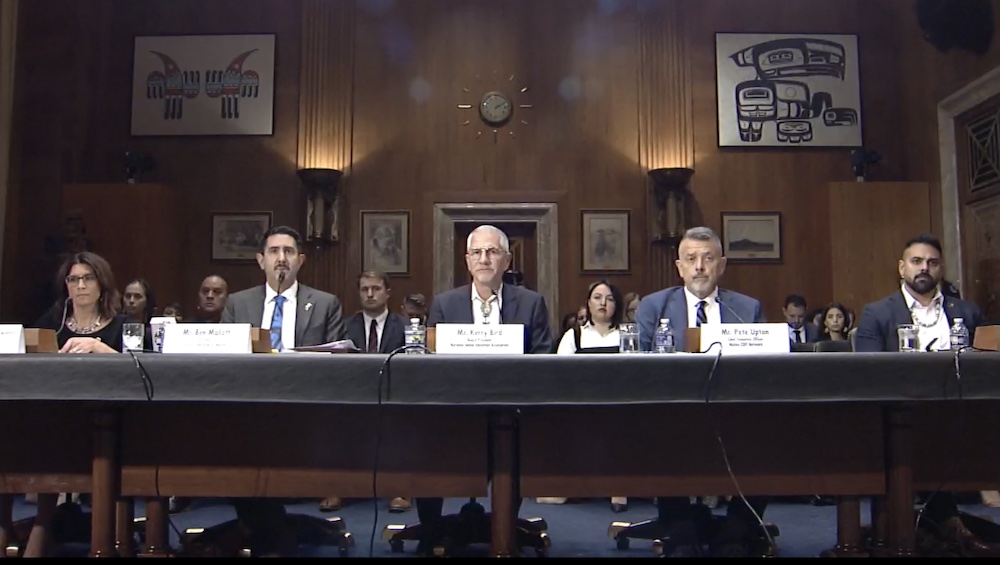

A prolonged federal shutdown and deep staff cuts are hollowing out essential Indian Country programs and breaking the government’s trust obligations, leaders told the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Wednesday.

During a committee hearing, witnesses testified that furloughs and reductions in force, or RIFs, have emptied the offices charged with carrying out the federal treaty and trust obligations, leaving tribes to fill gaps in food, health care, education and economic development. The shutdown has also severed consultation channels and halted the processing of grants, payments and technical assistance.

“Native programs are not DEI spending. They are not charity. They are the law,” said Sen. Brian Schatz, D-Hawaii, vice chair of the committee. “Attempting to cancel funds for Native programs, reducing more than 4,200 federal employees and eliminating tribal consultation policies—that’s not the United States government meeting its trust and legal obligations.”

The RIFs began on Oct. 10, eliminating thousands of federal positions across multiple agencies. At the Department of Education, the Office of Indian Education and the Impact Aid office were gutted. At the Treasury Department, the entire staff of the CDFI Fund was terminated, halting certification and funding processes for Native community lenders. Cuts at the Department of Health and Human Services hit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Health Resources and Services Administration, and other programs that support the Indian Health Service.

‘Flying in the dark’

Sarah Harris, vice chairwoman of the Mohegan Tribe and secretary of the United South and Eastern Tribes Sovereignty Protection Fund, said the federal government’s shutdown and staffing cuts have created chaos and silence.

“There’s been a complete lack of transparency,” she said. “No one knows what’s going on, and tribes can’t get in touch with their agency partners. Everyone is flying in the dark and just trying to do the best they can.”

Harris said the situation has forced tribes, including hers, to use their own limited revenues to subsidize federal benefits such as WIC and SNAP that tribal citizens are not receiving. “Ttribes are scrambling and spending their own time and resources to provide the most basic of human needs—food for their citizens,” she told the Senate panel.

She urged Congress to expand advance appropriations and make Indian program funding mandatory. “This is not about addressing poverty. It is about fulfilling commitments and promises,” Harris said. “Our funding is not discretionary—it is a debt prepaid with our lands and resources.”

Cascading impacts

Ben Mallott, president of the Alaska Federation of Natives, said the shutdown compounds the effects of Typhoon Halong and surging food costs. He said 66,000 Alaskans — including thousands of Alaska Natives — will lose SNAP benefits and that heating assistance payments are frozen.

With food costs already high—milk at $13 a gallon in some regions—families face stark choices, Mallott said. He also warned that canceled Federal Subsistence Board meetings threaten the governance of subsistence harvests, a critical food source for rural Alaska.

“Our people are about to be in the very real situation of having to pick between food and heat,” Mallott said.

Kerry Bird, president of the National Indian Education Association, said staff reductions have hollowed out the Department of Education’s Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. Staff reductions have left fewer than 100 employees, with the Office of Indian Education furloughed and at risk of elimination.That office administers $110 million in Title VI grants serving more than 400,000 Native students. Impact Aid, which provides $895 million annually to districts on federal and tribal lands, has also stalled.

Twelve tribal Head Start grantees serving 2,500 children face funding gaps. Johnson-O’Malley programs supporting 300,000 Native students in public schools are also frozen.

Pete Upton, CEO of the Native CDFI Network, warned that the shutdown and RIF that eliminated the Treasury’s entire CDFI Fund staff has frozen the financial system that underpins Native community lending. Before the reductions in force, he said, the CDFI Fund’s 81 employees managed roughly $6 billion in annual funding, overseeing grant awards, compliance reviews and certification that make Native CDFIs investable partners for philanthropic and private capital.

“With those staff members gone, there’s so much that’s not happening right now,” Upton said. He added that the lapse could shake confidence among outside funders. “That certification is the golden stamp that says you’re investable,” he said.

Native CDFIs, with average assets of $5.7 million, are often the only financial institutions in tribal communities, where 46% of residents live in banking deserts, he said, citing a Federal Reserve study.

Without the CDFI Fund’s Native American CDFI Assistance (NACA) Program, Upton said, capital for small business, housing and consumer lending in Native communities will collapse.

“The elimination of these funds would put us back 10 to 15 years on all the hard work that our Native CDFIs have done,” Upton said.

Healthy system strain

A.C. Locklear, CEO of the National Indian Health Board, highlighted the chronic underfunding of IHS. In 2023, IHS spending per patient was $4,078, compared to a national average of $13,493.

He noted that IHS hospitals average 39 years of age, more than three times the national average for U.S. hospitals.

While advance appropriations have kept IHS clinical services open during the shutdown, other accounts—covering sanitation, facilities, and lease payments—remain unprotected, Locklear said.

Across testimonies, tribal leaders asserted that shutdowns and RIFs are not temporary inconveniences but systemic failures that destabilize essential services. They called for expanding advance appropriations, reclassifying Indian program funding as mandatory, and reversing staff cuts that sever consultation channels.

“Congress’ failure to do our work, in my view, is inexcusable,” Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), chair of the committee, said during the hearing.” We’ve got to come together, which means we’ve got to talk to one another, and it can’t be about who’s winning, who’s losing, because right now, those that are losing are the American people, including the first Americans across the country.”