- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Policy and Law

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 promised unprecedented levels of federal funding for tribal projects. But crumbling infrastructure, lack of guidance and agency confusion have muddied the flow of dollars to tribal initiatives, according to Indian Country leaders at a Senate Committee on Indian Affairs roundtable Wednesday.

The roundtable’s witnesses fielded questions from the Committee, including chair Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) and vice chair Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska). Questions centered on emerging challenges as tribes attempt to access and utilize everything from guaranteed loans and grants to “game-changing” tax credits for energy projects.

“It's been over a year since both laws have passed and it's time to do some oversight on the implementation,” Schatz told the committee and witnesses. “Today, no matter what stage we are in, we want to make sure the implementation is progressing and meeting the needs of Native communities.”

Many of the concerns leveled during Wednesday’s meeting surrounded energy projects, which were meant to be bolstered by both bills.

For one tribe, the Hopi, an attempt to pursue a grant with the Department of Energy would have risked obliterating much of the tribe’s general budget thanks to a cost-matching measure.

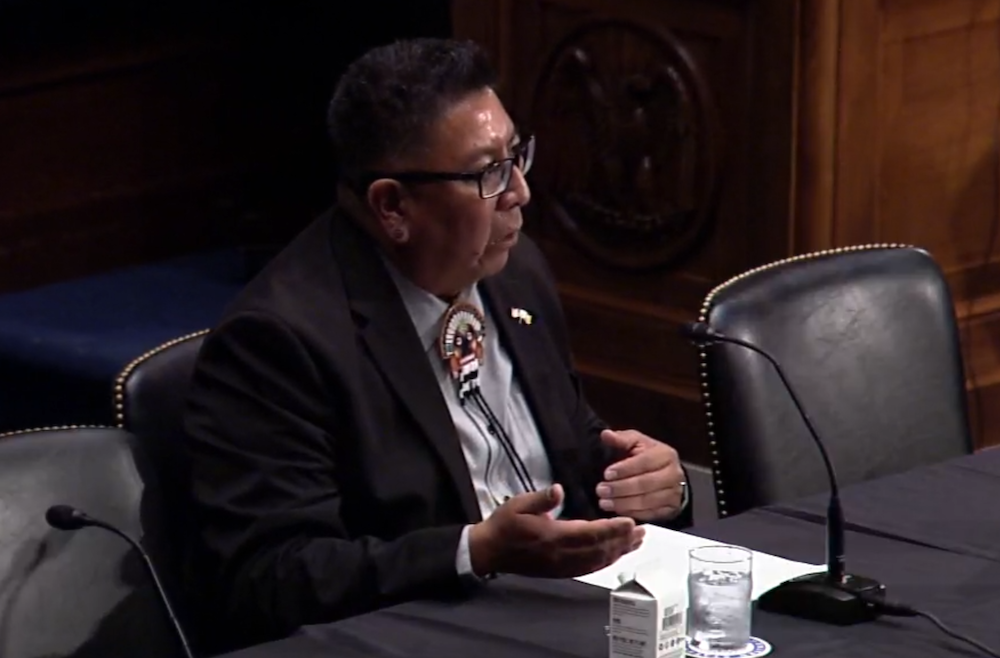

The project in question was a $50 million electrification project for Hopi residences, 85% of which remain unpowered, Hopi Chairman Timothy Nuvangyaoma told the Committee. The DOE’s initial ask for a cost measure of 50% was lowered to 20%. But that still left the Hopi tribe on the hook for $10 million - more than two-thirds of their annual general budget.

“We had to ask ourselves, do we shut down elderly services? Do we shut down the schools? It was a non-starter, really,” Nuvangyaoma said. “There's plenty of tribes that are small and don't have that voice here at the table today, so there's a lot of impact to tribes just like us who don't have that stability to make those cost matches and take advantage of such a great opportunity that's on the table for us.”

Senator Ben Ray Luján (D-NM) noted that the tribe had asked the Department of Energy waive the cost measure for the grant a month before a given deadline for the grant’s finalization, only to receive a response — a denial — four months later, well past the point of no return.

“Picking up the phone and answering questions is the simplest thing anyone can do,” Luján told the Hopi chairman. “I’m sorry. We’re going to see what we can do.”

Murkowski asked Jasmine Boyle, who represented the economic development nonprofit Rural Alaska Community Action Program in Anchorage, about the challenges in Alaska. Boyle said her organization had discovered many tribes couldn’t access the grant portals, much less the grants, and the infrastructure challenges only grew more difficult from there.

Funds from the American Rescue Plan Act and the CARES Act, implemented in the wake of COVID-19, were stifled by a lack of capacity and technology for many Alaska Native villages, Boyle said. Some tribes had just one person fielding requests, compliance audits, and grant proposals from multiple federal agencies. In other instances, tribes couldn’t receive necessary documentation because of federal policies requiring physical mailboxes at particular locations.

Even after funds were in place and projects were underway, issues like broadband connectivity impacted tribes’ ability to report compliance, which in turn jeopardized their funding, Boyle said.

Tribes need more agency support and technical assistance, she said.

“Each of these new tools [such as grant funding and technology improvements] is a building block, which we think will change the economic future for all parts of our state, but our communities don't have city planners,” Boyle said. “They don't have people to look at these blocks and build things out of them. They are taking this piece by piece and are very aware that with that connective tissue and additional assistance and support, they could build a new future that they have control over locally.”

Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma Chairman Jacob Keyes raised concerns about control during the discussion. His tribe’s recent pursuit of a grid resilience grant from the Department of Energy necessitated involving a utility provider.

Because the tribe lacks its own utility authority, Keys said the Iowa Tribe would be compelled to engage a third-party in their project, bleeding money from the grant funding, which, per the IIJA bill’s text, requires a 100% match already.

“We have a huge passion for working for the Department of Energy, creating things not just for our tribe but for the rest of Oklahoma,” Keyes said. “We really want the ability to use these funds the way that's best for our people, and the way they were intended to be used.”

Susan Masten, representing the Native American Financial Officers Association and its tribal members, voiced concerns shared by tribes attempting to access tax credits for their solar projects.

A lack of guidance from the Internal Revenue Service on how tribes can access these credits has pushed many potential projects into a “holding pattern,” Masten said. To mitigate the uncertainty, some tribes have been asked to form corporations or new, taxable entities to claim the credits — a requirement that poses challenges, particularly for smaller tribes.

“The IRS needs to provide guidance that recognizes the tax-free status of tribal governments and entities,” Masten said.”This is especially crucial for tribal energy development, where partnerships and corporate structure can make or break the viability of a given energy project. The question needs to be answered now. We can't wait any longer. It's not fair and it's delaying our project development."

Schatz agreed, and said that the IRS was not there to litigate whether or not Native entities were eligible for the credits.

“Individuals can have their view, but once Congress has spoken the discretion is not there to say, ‘Well we'd like to go ahead and form this new entity,’” Schatz said. “I think agencies are not used to working with Native people and Native entities. For them, it's a square peg (in a) round hole, and so what they do is try to get you to resemble the thing they're accustomed to. That is not what they're supposed to do.

“We've made laws, we've put historic resources behind them, and it is not up to an agency civil servant to withhold those resources.”