- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Energy | Environment

The Tule River Economic Development Corp. is deploying a $14.7 million Environmental Protection Agency grant to build a biochar facility in California’s Central Valley, positioning the tribe to generate renewable electricity and tap into carbon credit markets.

The plant, planned for a former cotton gin site near Tipton, is expected to process up to 31,500 tons of woody biomass annually, producing about 4,500 tons of biochar and roughly 4,000 megawatt-hours of renewable power each year, according to TREDC estimates.

At current voluntary carbon market prices of about $150 per ton, each ton of biochar — representing roughly one ton of carbon dioxide removed from the atmosphere, depending on carbon content and application — could create an additional revenue stream alongside electricity sales and agricultural distribution.

Thomas E. Wilbur, chief executive officer of TREDC, said the project grew out of a federal Climate Pollution Reduction Grant the tribe pursued as environmental pressures intensified across the Central Valley.

Thomas E. Wilbur, CEO of Tule River Economic Development Corporation“We took up the banner through the EDC for the tribe,” Wilbur said. “We see a huge amount of potential waste out there, and we wanted to put that to use.”

Thomas E. Wilbur, CEO of Tule River Economic Development Corporation“We took up the banner through the EDC for the tribe,” Wilbur said. “We see a huge amount of potential waste out there, and we wanted to put that to use.”

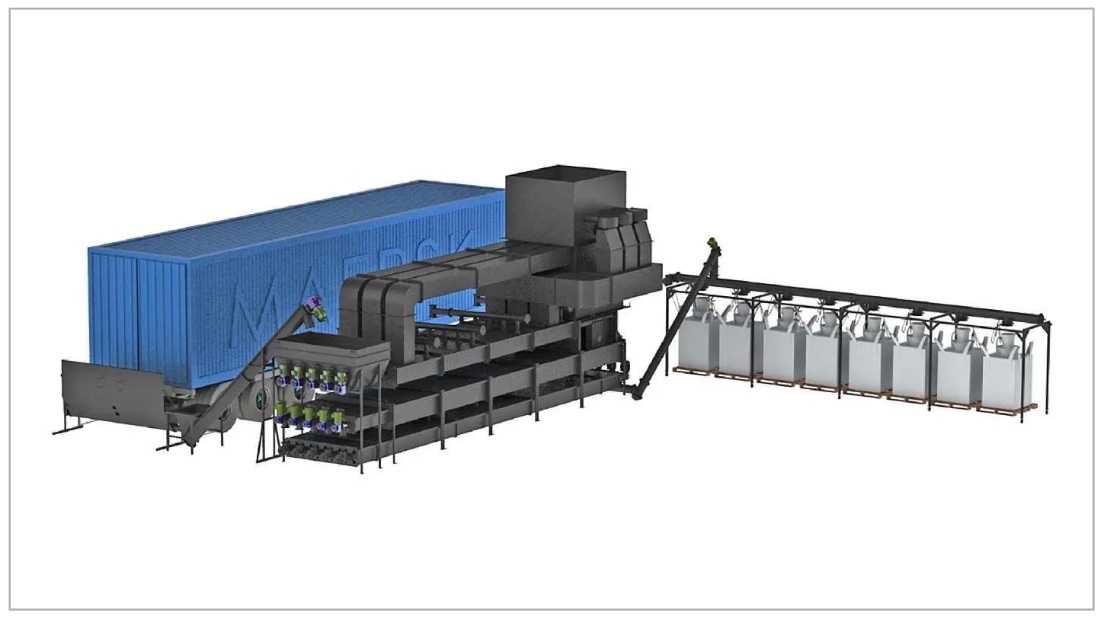

The facility will use pyrolysis technology developed by ARTi, a five-unit system that heats biomass in low-oxygen chambers to convert it into biochar, a stable, carbon-rich material used to improve soil health and water retention. After an initial injection of natural gas, the system recycles its own heat, converting hydrogen and carbon monoxide into electricity.

Vanessa Felix, quality assurance manager and project manager, said the system is designed to handle a wide range of woody material.

Biochar’s porous structure improves soil health, increases water retention and can sequester carbon for hundreds to thousands of years. TREDC plans to sell the product to growers across the region and use it in local agricultural soils.

“It’s good for the earth,” Felix said. “We plan to put it back into the agricultural soils to improve crop yield, and of course provide jobs for the nearby community and the tribe. For us, it’s not necessarily waste, because this product can be used to create value.”

Biochar stores carbon because the heating process transforms plant material into a stable, carbon-rich solid. Studies tracking biochar in farm soils have found that most of this carbon remains in place for years, with limited change even after more than a decade of tilling and fertilizing, according to a report published in Agronomy, a peer-reviewed agricultural journal. Researchers also found that adding biochar can increase total soil carbon while improving water retention and nutrient retention.

In addition to improving soil quality, biochar could open a new market for the Tule River tribe: carbon credits. Carbon credit programs classify biochar as a long‑term carbon‑removal method because the carbon it contains is locked into a solid form rather than released into the atmosphere, according to the Agronomy report.

The facility is projected to remove up to 10,600 metric tons of carbon dioxide annually — equivalent to taking about 4,800 gasoline-powered vehicles off the road — according to TREDC projections.

ARTi’s pyrolysis reactor (top) converts woody biomass into biochar (bottom), a carbon-rich material used to improve soil health and store carbon long term. (Image courtesy of ARTi)

ARTi’s pyrolysis reactor (top) converts woody biomass into biochar (bottom), a carbon-rich material used to improve soil health and store carbon long term. (Image courtesy of ARTi)

Raw material is not expected to be a problem. TREDC plans to source material from both the Sierra Nevada and the surrounding agricultural corridor. Orchard trees reach the end of their productive life every 20 to 30 years, leaving behind large volumes of woody waste, Wilbur said.

“We’ve got piles and piles and piles of wood that can be used for biochar, and we’ve figured out a good way to make use of it,” Wilbur said.

TREDC expects the facility to create about a dozen jobs, with opportunities for tribal citizens as operations expand. Wilbur said the project is part of a broader effort to diversify the tribe’s economic base and strengthen its sovereignty through tribally driven climate and energy projects.

Liam Huber, an Energy Innovator Fellow working with TREDC, said that California state air quality rules now prohibit farmers from burning woody material — a restriction that has increased the buildup of biomass and demand for alternative disposal methods.

“You see turnover in crops that results in biomass that you have to get rid of, and they can no longer burn it,” Huber said. “By investing in this facility, we’re hoping that we can tap into that waste stream and divert that biomass from becoming air pollution.”

The Central Valley’s agricultural sector is only part of the feedstock. Through a co‑stewardship agreement with the U.S. Forest Service, the tribe expects to receive non‑salvageable softwood from the mountains east of the reservation. Felix said the site near Tipton was chosen in part because of its access to both regions.

“When you think of east‑west, the site is situated with easy access to the forest,” she said. “That made us a good choice for the grant.”

Huber said the EPA’s investment reflects the project’s potential to scale and deliver regional benefits.

“This is why the EPA decided to give $14.7 million,” he said. “Because of that scalable potential to bring down air pollution.”