- Details

- By Rob Capriccioso

- Economic Development

WASHINGTON — The federal government needs to invest $300 billion annually in Indian Country to fully promote and support economic development.

That jaw-dropping figure from tribal leaders came in response to a question posed by the Biden administration during the White House Tribal Nations Summit on Nov. 16 about what it should be doing to help Indian Country. Such an investment would easily dwarf any amount that has ever been proposed or provided yearly to tribes collectively by the federal government.

Even the unprecedented $32 billion in pandemic relief funding this year, plus the approximately $13 billion for Native nations under the bipartisan infrastructure deal, coupled with the customary budget-appropriated funding, does not come close to approaching that number.

Want more news like this? Get the free weekly newsletter.

Tribes have also requested a 5 percent set-aside of the new spending in the Build Back Better reconciliation plan under consideration in Congress, and they are requesting a 5 percent set-aside of the $28.6 billion disaster relief bill the Biden administration is currently advancing.

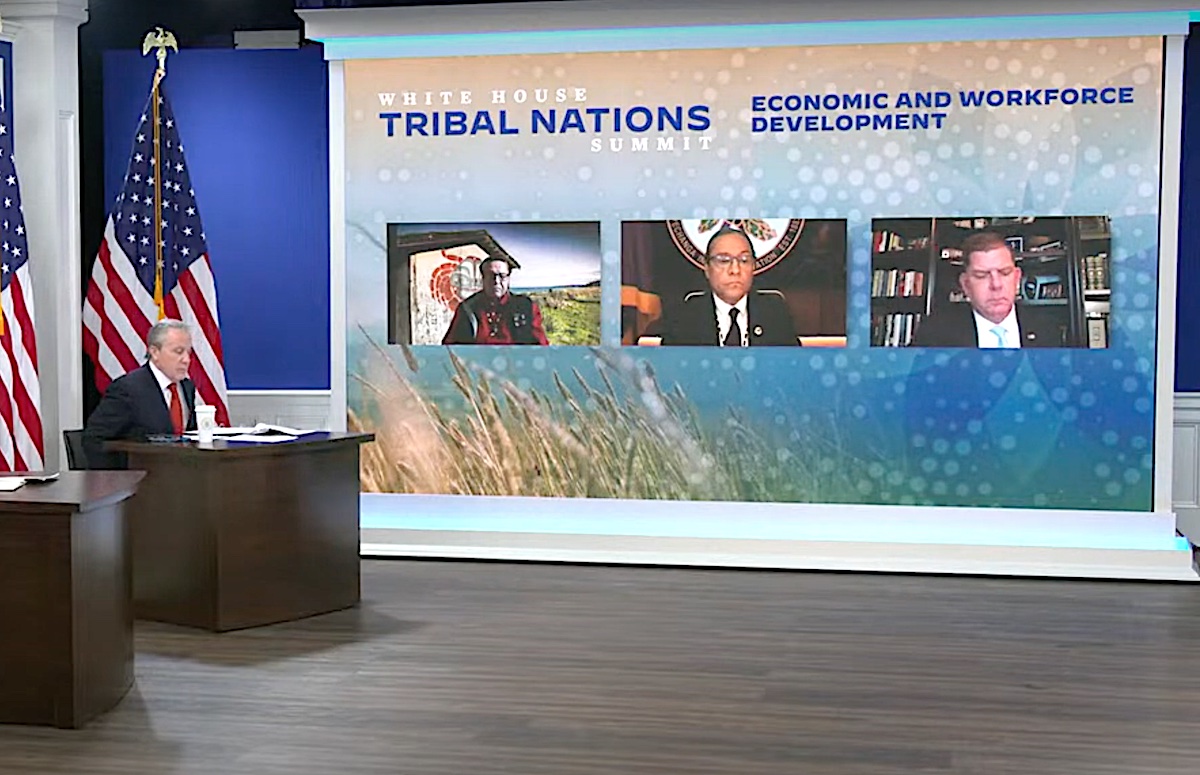

“What I believe, and I think my colleagues believe, firmly, that the true need of our 574 Indian nations, from Alaska to Florida, there probably is (a need) north of $250 or $300 billion annually,” W. Ron Allen, long-time chair of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, told a panel of top administration staffers. They included Gene Sperling, senior adviser to President Joe Biden; Marty Walsh, secretary of the Department of Labor; and Isabelle Guzman, administrator of the Small Business Administration.

“That tells you we’ve got a ways to go to fulfill the true needs of our communities,” he said in perhaps the understatement of the year. “The question is: How do we get there?”

Allen, who is also a long-time, savvy leader with the National Congress of American Indians, perhaps wanted to shock and awe with the $300 billion figure, and he quickly followed up that notation with the fact that tribes are well aware of the American government’s massive deficit. He additionally said that U.S. Office of Management and Budget figures suggest tribes have received about $28 billion in annual federal funding over the last 10 years.

“So is the federal government ever going to come up with the resources that will meet that $250-$300 billion (need)?” Allen asked. “The answer is no. It just can’t get there. So the question is, ‘How do we get there?’”

Allen argued that tribes must have an agenda of “self-reliance” in combination with any governmental funding that might come along as part of federal treaty and trust responsibilities. Indian gaming has been a useful tool for some, he noted, and he welcomed pandemic funding to tribes under the CARES Act, the American Rescue Plan Act, and current proposals for infrastructure and disaster-relief infusions.

“As we try to move our tribal governments forward to be more self-reliant and not depend on the federal government — not that we would ever release the federal government from its treaty … and moral obligations to Indian Country — in order to fill that gap, it’s going to be our economic arm,” Allen said.

“When you think of the 574 Indian nations, we’re complicated,” Allen continued, noting an issue that federal agencies often have a difficult time understanding. “We’re large, and we’re small — large land-based, small-land-based, large numbers of tribal citizens, small numbers of tribal citizens, different levels of sophistication.”

“Quite frankly, the administration needs to step up to assist the tribes (especially) for those who need more assistance in elevating their political, legal infrastructure so that they can go out and secure the resources that they need, or utilize the existing resources the administration is providing them to allow us to be able to move our economic arm forward,” Allen said. “Each of us will come up with what works for us — what businesses, what enterprises will work for us. Most of us are trying to diversify our economic portfolios. … Most of us are rural in communities, for the most part, and so now we’re trying to figure out how to recruit and retain professionals and talent in order for our business to be a success.”

Mark Macarro, chairman of the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians, said during the summit that tribal nations are building strong economies and investing in their communities by supporting the development of Native-owned businesses and providing tools and resources to their citizens.

“(T)here are still (federal) barriers that are out there right now that are necessary to be overcome,” Macarro said. “Interagency cooperation, regulatory changes that incorporate tribal priorities and increased access to capital are all ways that (positive) changes can be accomplished.”

Macarro suggested that as a baseline, the Biden administration should “continue to ensure that any initiatives to support economic development in Indian Country are a result of engagement and consultation with Indian Country.”

Plenty of consultation initiatives have been highlighted by the Biden administration before, during and after the summit, including new efforts and a tribal committee within the Interior Department, as well as a goal to improve interagency efforts through increased transparency of the White House Council on Native American Affairs.

“The pandemic has placed our tribal governments and enterprises on shifting sands, forcing all of us to be nimble and flexible as we find new paths forward to support and protect our communities,” Macarro said. “While Indian Country has found some success in building our economies, there are key actions that could be taken to foster our efforts and remove remaining impediments.”

Along those lines, Macarro said the administration should continue to support the modernization of tribal governmental bond issuances on a par with state and local governments and facilitate tribal infrastructure development and financing of tribal projects.

“You’ve heard much about the need to both fund and incentivize the development in Indian Country’s telecommunications infrastructure, particularly access to broadband,” Macarro noted. “This infrastructure is critical as we seek new opportunities in the changing economy and modernize our access to health care and education.”

Permitting for such endeavors must include Indian Country in the planning process from the outset, Macarro added.

Tribes also have a need to regulate their own labor rules, Macarro said, adding that many feel the National Labor Relations Act needs to be amended to address tribal sovereignty. He further recommended that the administration “refocus efforts on approving revised Indian trader regulations, which will allow tribes to keep tax revenues generated on the reservation.”

Addressing dual taxation in Indian Country, which involves state taxation of business activities in Indian Country, is another goal he highlighted for the administration.

Affordable child care programs, housing for tribal workforces, flexibility in training and technical assistance programs focused on workforce development were other areas tribal leaders suggested could provide aid given current tribal economic conditions.

To improve tribal economic development, leaders suggested the federal government could do better at data collection involving tribes and provide support for climate resiliency. Multiple leaders also pressed for flexible rules involving the spending of tribal infrastructure funds under the bipartisan infrastructure deal.

Tribes also want to carefully consider the effects of infrastructure funds in Indian Country going to non-tribal entities. No tribe wants to be negatively affected as a result of new infrastructure activities that infringe on their treaty or sovereign rights, as has happened in the past on various issues, including pipelines.

Gene Sperling, senior adviser to President Joe Biden, suggested that tribes use some of their monies received under ARPA to help with workforce retention and development until more funding potentially comes on that front under the Build Back Better Plan, which is still being negotiated by Democrats in a reconciliation bill in Congress.

“I believe … the Build Back Better plan will pass, but there’s a lot of ways to use those state and local funds (under ARPA) as your bridge,” Sperling said. “You can have full flexibility in designing those labor market job programs, workforce development, apprenticeship programs, and I would encourage more people to look at those funds.”

Whether Sperling and other top administration officials truly comprehend the unique political and sovereign realities of tribes and how these realities tie into their economic goals remains to be seen. But tribal leaders at the summit vowed to continue their education efforts.