- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

- Arts and Culture

Cherokee author Traci Sorell is at the top of her game right now.

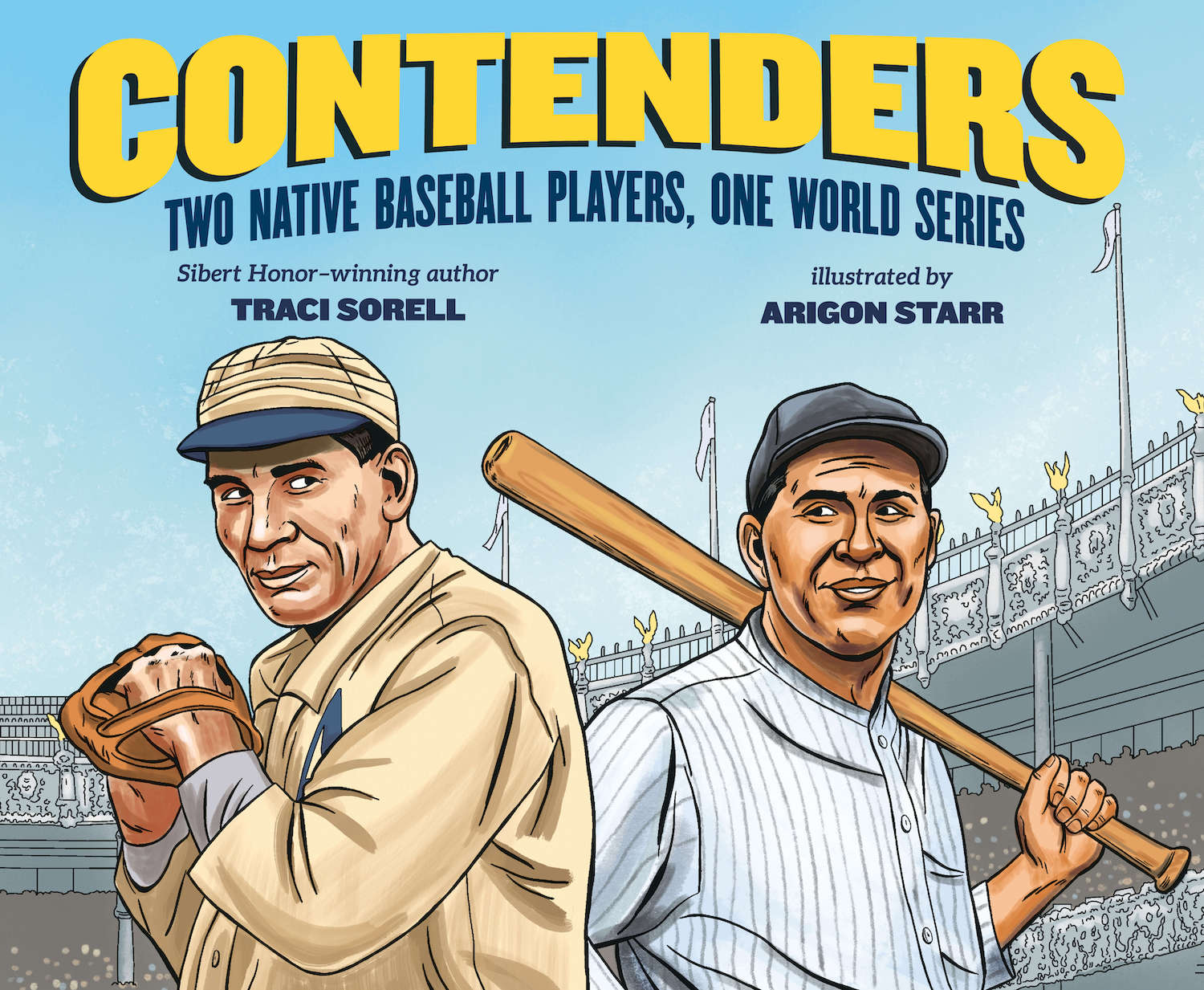

Lately, the award-winning trade children's book author is out and about promoting her latest release Contenders: Two Native Baseball Players, One World Series and hitting back against book bans with NPR interviews, and presentations at the Texas Library Association conference and the Pen America World Voices Festival in New York City.

“The reason trade books exist is to provide reading beyond what's in the curriculum. We're a huge supplement in people's homes as well as in the schools in the library and in the classroom,” Sorell told Tribal Business News. “There are a lot of pieces to it and I enjoy it: to create something, to lose myself in a story, engage with craft, do the research, and to visit with other people. I love visiting with young people, librarians and teachers, whether it's at a school or a workshop, or when I'm doing a keynote at a conference.”

Contenders, which is Sorell’s eighth book, takes readers out to the ballgame and immerses them in the stories of Ojibwe pitcher Charles Bender and Cahuilla catcher John Meyers, who played on opposing teams in the 1911 World Series.

Author Traci Sorell (Photo: Cody Hammer)

Author Traci Sorell (Photo: Cody Hammer)

Sorell doesn’t soften the reality for young readers. She honestly and accurately shows how a constant barrage of racism and disrespect undercut the Native players’ achievements.

“As I talk about in the book and the timeline, there are still people playing right now in Major League sports that can't just go to work and not have their culture and their heritage mocked,” she said. “There is a Choctaw and a Potawatomi player on the Kansas City Chiefs. So there's not a game that they're out playing that people aren't doing that stuff. It's sickening that that's the environment they’re working in.”

Simply telling the truth about the treatment of Native people then and now — or centering Indigenous people and culture at all — is a threat to those who want to whitewash education, she said. And that’s where another crucial element of Sorell’s career comes into play: banding together with fellow authors to battle book bans.

“What I've been able to ascertain is that censors take books created by BIPOC or LGBT (authors) that end up on awards lists and are receiving recognition, and that's what's getting banned. They don't even take the time to read the books,” said Sorell, who herself has had three books end up on banned lists. “This is a national issue with some gatekeepers limiting access to books that help young people see themselves, their peers and the world around them.”

The influential, unflinching and authentic culture warrior and writer didn’t take the conventional route to the publishing industry.

“People think I was an English or creative writing major. I didn't do any of that stuff,” Sorell said. “I never set out to do this, and that's the thing that I tell students when I do author visits at schools. There are many pathways, and you can do many things over the course of your lifetime if you want to.”

Sorell, whose background is in Federal Indian Law Policy, came to publishing with years of wisdom and experience gained through high-level positions in some of the most influential and effective nonprofits and organizations in Indian Country.

Her previous jobs include posts as legislative director for the National Indian Health Board in Washington, DC and executive director for the National Indian Council on Aging. Her work included writing grants, helping with fundraising proposals and establishing tribal courts.

In 2013, she started experimenting with writing childrens’ books. The desire to create Native stories for kids from a Native perspective was sparked while Sorell was majoring in Native American Studies at University of California Berkeley in the ‘90s and taking a class dealing with representation of mixed race children in books

“From that point on, whenever I would go to a museum or bookstore, I would always look at the books they have about Native people. And they were largely books around, traditional stories, but that had been retold, reimagined and illustrated by non-Natives,” she said. “And then there might be a few biographies of people or some historical events, but not written in the dynamic way that non-fiction for young people is written now.

From 2013 to 2015, Sorell balanced her consulting business with developing her writing skills. She worked on stories, sent them out for critiques, attended kids literature conferences and checked out tons of books to study structure and style.

“I was essentially giving myself an MFA in creative writing,” she said. In 2015, bolstered by great feedback at workshops from folks in the industry, she decided to make writing her career focus. Her husband had a full-time job, so she could channel her energy into her publishing goals without worrying about paying the bills.

Her first published book — We Are Grateful, illustrated by Frané Lessac — is a glimpse into the Cherokee customs and challenges that accompany each season of the year.

“I was looking at doing a book that shows us in our contemporary lives, doing the things that we do and showing what we value,” she said. “It's not like this fast-paced thriller. It is literally just Cherokee people living our lives.”

That simple, well-intended formula became what the publishing industry calls an “evergreen classic.” It sold more than 100,000 copies and laid the groundwork for all the other books she wrote to do well, Sorell said.

“Having that book come out of the gate so strong definitely helped. The things that were acquired after that and in process before that came out, got a lot of push and help and attention to them. I’ve worked to maintain the quality of craft and not with the expectation that everything will be a home run. But to be perfectly honest, it has been really good.”

Sorell didn’t even have an agent when We Are Grateful was purchased. But she did have a pro in her corner. Sorell won a coveted critique and some suggested notes from a prolific writer prior to sending it out to publishing houses.

“She said ‘You need to get this out in the world,’” Sorell said. Within a month, she sent the book to 10 different publishers and got three letters of interest. Three months later, she sold it to Watertown, Mass.-based children’s book publisher Charlesbridge.

“Getting that first book sold on my own did help me get an agent,” she said. “Since then, I've done books with a number of different publishers, but Charlesbridge and Penguin are the main two that I’ve worked with consistently.”

Sorell is quick to point out that her books benefit greatly from Cherokee community support.

“Bookmaking is a team sport. Cherokee culture keepers, wisdom keepers, historians, first language speakers and all kinds of folks help me before I even submit a manuscript,” she said. “We have full Cherokee language editions of my books that we've been able to put out, and everybody is just wonderful about sharing their knowledge and helping me fill in the gaps.”

The generosity goes both ways. Mentoring and uplifting aspiring Native authors and artists comes naturally to Sorell, who is set on changing the way publishers treat Indigenous illustrators.

“Until very recently publishers have not worked with actual Native people to illustrate our stories,” Sorrel said. One of the first things she did coming into the industry was to look at all the different Native illustrators and artists that she might be interested in working with on projects. She compiled a Word document with all their contact information and began emailing it to editors at publishing houses to encourage them to hire Natives.

With all her writing and appearances, as well as her ongoing efforts to fight toxic censorship culture and cultivate a new generation of Indigenous authors and illustrators, it’s essential for Sorell to also schedule some downtime.

“Like with any other job, people always want you to do more. So you have to ask yourself, ‘Where are my boundaries?’” she said. “You need to know the season of life you're in and what your body, mind and spirit need. Because if you don't nurture that, especially in a creative field, you will get depleted. You will get burned out.”