- Details

- By John Wiegand, Special to Tribal Business News

- Real Estate

Floors collapse beneath residents’ feet. Black mold infestations that trigger respiratory illness. Homes so deteriorated they can’t keep out harsh South Dakota weather. On the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, Ellen White Thunder sees beyond dilapidated buildings to the root cause: homes fundamentally compromised from day one.

“The majority of the homes, visually, are a reminder of … why things should be built solidly and sustainably from the start,” White Thunder, the deputy director of Lakota Funds, told Tribal Business News.

Now, she and others across Indian Country are tackling this persistent problem with a solution that may seem dry as toast to outsiders, but could transform housing on Pine Ridge and other tribal nations: building codes.

For many people, those two words elicit 1000-yard stares or grumbles about tedious paperwork, regulatory hurdles and added cost. And for Native communities without them, the idea of creating, implementing and enforcing these building codes may seem like the last priority on a long list of housing needs.

Yet, dozens of Native communities across the country have turned toward building codes to spur economic development, improve health and exercise sovereignty on their lands.

[RELATED-Q+A: Matthew Beaudet on building codes as an exercise of tribal sovereignty]

Without building codes, tribes rely on the discretion of contractors – and manufacturers, in the case of modular housing – to build to modern standards with materials appropriate for the climate and conditions. However, tribes with no codes or enforcement mechanisms are routinely taken advantage of by contractors who use cheap or cast-off materials, employ shoddy building techniques and skimp on essential elements like insulation, ventilation and frost protection.

This dynamic often leaves Native families and communities holding the bill for dwellings that are inferior to those they paid for.

Thirty-four percent of Native American and Alaska Native households had one or more physical problems (plumbing, electrical, kitchen deficiencies, etc.), compared to 7% of U.S. households, according to a housing needs study conducted between 2011 and 2016 by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. This data, while dated and limited in scope, represents one of the few comprehensive studies available on housing conditions in Indian Country, where data collection is often challenging.

These physical problems will likely worsen as substandard construction practices and overcrowding continue to stress homes across Indian Country.

Sources say that contractors often prey on tribal communities without building codes or justice systems to hold them accountable.

“You’re getting a lot of shady contractors that take advantage of tribal communities,” said Daniel Burr, a member of Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans and vice president of Native American Code Officials (NACO). “They’ll come in and want to get paid, but they’re whipping that product out and leaving.”

To begin addressing these issues, White Thunder and Burr joined a coalition of three other building inspectors and code officials from across Indian Country to create NACO in late 2023. The organization has grown to 62 members. In October 2024, NACO was officially recognized as a chapter of the International Code Council (ICC) at an ICC board meeting held in Long Beach, Calif.

Representatives from 19 tribal nations gathered Dec. 2024 at the History Colorado Center for the historic Summit on Model Building Codes focused on tribal sovereignty, safety, and economic empowerment. (Photo: Daniel Jackson)

Representatives from 19 tribal nations gathered Dec. 2024 at the History Colorado Center for the historic Summit on Model Building Codes focused on tribal sovereignty, safety, and economic empowerment. (Photo: Daniel Jackson)

The decision marked the first time the ICC, a non-governmental organization that sets standards for residential and commercial buildings across the globe, recognized an indigenous chapter, creating a new category known as “Sovereign Chapters.”

ICC’s codes are not law but are widely considered the industry standard. Many states and municipalities adopt all or portions of the ICC’s codes to set their own building standards. When the founding members of NACO first contacted ICC about building codes on tribal land, the organization realized it was missing an important voice.

“We need to make sure building codes have voices that are heard,” said Richard Hauffe, senior regional manager of government relations at ICC. “That the implementation of (codes), as well as the development, have Native voices.”

The Case for Codes

Reasons vary among tribes apprehensive of building codes, but sources say most Native communities avoid regulations out of distrust for influence and policies that originate outside the tribe.

“Tribes have had a hard time being taken advantage of by the federal government in the past,” Burr said. “It’s a thing they feel that (they) don’t want to trust that person or that agency. We don’t know if they’re coming in there just to get work or push their product.”

NACO and the ICC say they acknowledge that dynamic, categorizing ICC codes as a menu of tried and tested options rather than an all-or-nothing rule book. Tribes can choose to adopt the codes that best fit their communities and disregard those that don’t.

As a former building inspector and enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Community, David Jackson is careful to avoid pushing tribes one way or another when it comes to codes. Instead, Jackson, who serves as NACO’s president and operates his own consultancy, Code Advisory Group, refers to his work as “delicate mutual respect.”

“When a tribe is emerging into the code realm, I want to help them develop their awareness, increase their technical proficiency and find a way that works best for that community,” he said. “I do not dictate how things should be done for their community.”

David Jackson highlights items to watch out for during inspections to Duck Valley Housing Authority members during a site visit in Idaho. As NACO president and enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Community, Jackson emphasizes his approach of 'delicate mutual respect' when helping tribes develop building codes that work for their specific communities. (Photo: Richard Hauffe)

David Jackson highlights items to watch out for during inspections to Duck Valley Housing Authority members during a site visit in Idaho. As NACO president and enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Community, Jackson emphasizes his approach of 'delicate mutual respect' when helping tribes develop building codes that work for their specific communities. (Photo: Richard Hauffe)

Instead of breaching sovereignty, proponents of building codes see the regulations as a way for tribes to flex sovereignty by controlling what is built, how it is constructed and giving them an enforcement mechanism to fine contractors, if necessary.

“There’s no greater way to get a contractor in line (than) when you start hitting the checkbook,” Jackson said.

That ability to exercise sovereignty is part of the reason why the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi established their own building codes in 2002. The tribe based their building codes first on Michigan’s before changing over to the ICC in 2012 to better accommodate their geography, which spans Michigan and Indiana.

Building codes allow Pokagon to hold contractors to its own standards for projects built on land the tribe holds in trust. For projects outside trust land, having experience with building codes and enforcement helps avoid non-Native building inspectors putting a “rubber stamp” on Pokagon’s projects, said Anthony Foerster, the tribe’s residential building official.

“(They) don’t put into it what they need to put into it, because there’s just been so many things they overlook,” Foerster said of non-Native building inspectors on Pokagon projects. “They just assume they don’t have to worry about the liability because it’s not their land.”

Pokagon put its knowledge of building codes to good use when it acquired two apartment complexes totaling 96 units on fee land in Dowagiac, Mich. When the tribe purchased the properties in 2022 to address a shortfall in housing for its members, the buildings were in rough condition. Decades of nicotine stains, poorly maintained exteriors, and outdated electrical panels that caused fires in some units and other problems plagued the building.

Building A of the Pokagon Band's $6 million apartment renovation project, transforming units that once suffered from decades of nicotine stains, fire-causing electrical panels, and deteriorated exteriors. The renovated complex in Dowagiac, Michigan now features modernized systems and ADA-compliant units for tribal members. (Courtesy photo)

Building A of the Pokagon Band's $6 million apartment renovation project, transforming units that once suffered from decades of nicotine stains, fire-causing electrical panels, and deteriorated exteriors. The renovated complex in Dowagiac, Michigan now features modernized systems and ADA-compliant units for tribal members. (Courtesy photo)

Pokagon invested nearly $6 million to renovate the buildings to modern standards and turn several apartments into ADA compliant units. Pokagon funded half the project through a Indian Housing Block Grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The tribe self-funded the remainder of the project.Construction is slated to conclude in spring 2026.

Having building codes also equips Pokagon to ensure their housing meets the health and safety needs of its community members, particularly its elders. In some developments, the band has built or renovated units to accommodate wider doorways, living rooms large enough for hospital beds and installed backup generators. Townhomes in the band’s tribal village, Pokégnek Édawat, include bathrooms that double as storm shelters – made with six-inch thick concrete and steel doors – that can withstand an F5 tornado, Foerster said.

Indigenous-Driven Construction

Traditional methods of construction — like building with clay and mud — are making a comeback in architectural, engineering and mechanical professions.

NACO members hope their relationship with the ICC will also flow the opposite way, helping set standards for traditional structures that other tribes can use if they choose, said Matthew Beaudet (Montauk Tribe of Indians), the former building commissioner for Chicago who also serves on NACO’s board.

“This is where Indian Country is teaching the ICC,” Beaudet said. “You’re not going to find an ICC code on sweat lodges. Eventually we’ll just tell them, now that we have a voice with the ICC.”

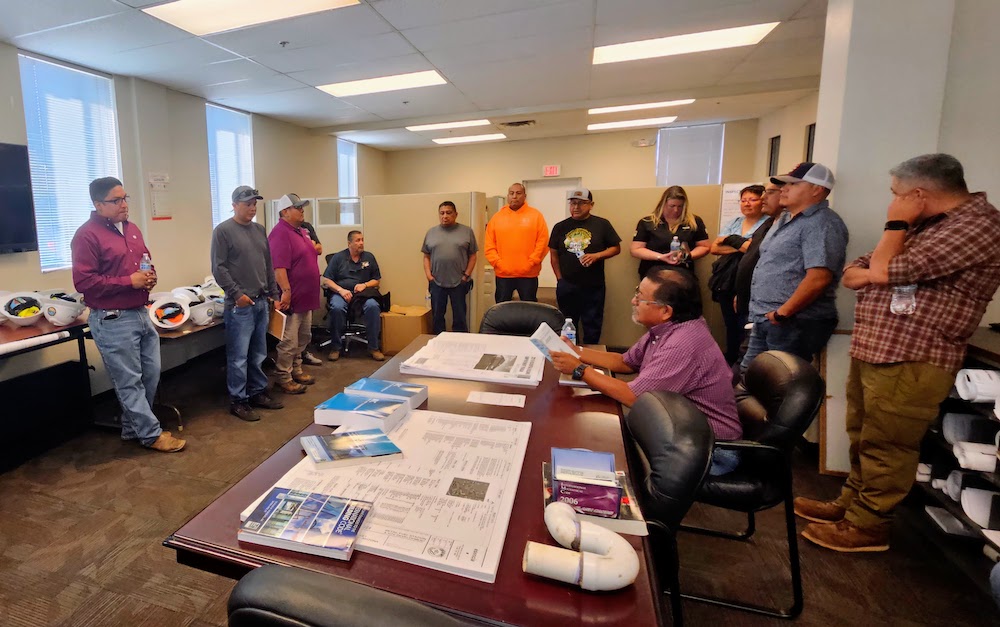

Members of the Southwest Tribal Housing Alliance gather for training on building code implementation at Gila River Housing offices. This collaboration exemplifies how Native communities are developing construction expertise that honors both modern safety standards and traditional Indigenous building techniques. As tribes reclaim control over construction practices, these discussions ensure buildings meet community needs while preserving cultural identity. (Credit: David Jackson)

Members of the Southwest Tribal Housing Alliance gather for training on building code implementation at Gila River Housing offices. This collaboration exemplifies how Native communities are developing construction expertise that honors both modern safety standards and traditional Indigenous building techniques. As tribes reclaim control over construction practices, these discussions ensure buildings meet community needs while preserving cultural identity. (Credit: David Jackson)

But Daniel Glenn (Crow), principal architect of Seattle-based 7 Directions Architects/Planners, worries that creating standards for traditional structures could limit a tribe’s ability to express their unique cultural identities. Design and construction methods of traditional structures vary widely across (and even within) tribes and are passed down through generations, making them challenging to codify.

“It’s a dangerous path to follow for traditional structures,” Glenn said, noting his firm follows ICC code for non-traditional construction elements. “As part of sovereignty, each tribe has to have the ability to build their own traditional structures without the intervention of any sort of code body, regardless of that body.”

7 Direction Architects often incorporates Indigenous construction methods and elements in its designs. The firm used traditional timber framing methods to construct the roof of its Nageezi House, a residential home built on the Navajo Reservation, with locally-sourced lumber.

Typically, lumber is officially graded by inspectors before it is sold for construction. 7 Directions Architects used ungraded lumber and did not follow building codes for timber framing, however, the firm did hire a third-party structural engineer to ensure safety.

Similarly, Pokagon created an indoor fire pit to conduct ceremonies in their tribal court building without building codes. Instead, the tribe relied on its own design and enlisted the help of engineers to make sure the fire pit would function properly and be safe to use.

Laying the Foundation

Back on Pine Ridge, White Thunder and Lakota Funds are working around the lack of building codes on the reservation while also preparing for a future when they are a reality.

Lakota Funds, a Native community development financial institution (CDFI), requires businesses that borrow funds for commercial development projects to follow ICC’s 2018 building codes. Lakota Funds also requires inspections on residential projects and that residential contractors are checked for liability insurance, workman’s comp and other requirements.

Ellen White Thunder, Lakota Funds Deputy Director, champions building codes to improve housing on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. (Photo: Lakota Funds) White Thunder also oversees a building inspector training program for tribal members across South Dakota to become state-certified inspectors. So far, the program has helped certify 17 Indigenous people across six of the state’s nine reservations. When White Thunder and her team began the work in 2022, there were two certified inspectors on two different reservations in the state. Lakota Funds uses these certified inspectors on its projects.

Ellen White Thunder, Lakota Funds Deputy Director, champions building codes to improve housing on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. (Photo: Lakota Funds) White Thunder also oversees a building inspector training program for tribal members across South Dakota to become state-certified inspectors. So far, the program has helped certify 17 Indigenous people across six of the state’s nine reservations. When White Thunder and her team began the work in 2022, there were two certified inspectors on two different reservations in the state. Lakota Funds uses these certified inspectors on its projects.

The inspector training program was funded through a $5 million “Good Jobs” grant through the U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA).

To White Thunder, oversight through building codes is an economic development and social priority, especially as Pine Ridge manages the construction of multi-million-dollar federal projects.

“It’s very important for tribes to have commercial building codes in their communities to protect their children and their elders in these community facilities that are built using federal grants,” she said.

NACO’s leadership plans to continue to push the organization forward, both by increasing membership (NACO has 62 members) and increasing its presence as an Indigenous voice in building safety and construction. The organization also plans to expand its reach beyond the building industry, taking its message about building codes to Native American conferences on health and aging.

Jackson, NACO’s president, put the organization’s outlook succinctly: “For NACO, the sky is the limit.”