- Details

- By Mark Fogarty

- Real Estate

Tribes that apply for expedited leasing authority can flex their sovereignty to remove bottlenecks that get in the way of tribal members receiving mortgages.

Members of the New Mexico Tribal Homeownership Coalition heard case studies from the Pueblos of Isleta and Jemez, both located in New Mexico, about their experience with the Helping Expedite and Advance Responsible Tribal Home Ownership (HEARTH) Act, which allows tribes to run their own residential leasing programs.

Tribes also can seek leasing authority for business, wind and solar, and agricultural purposes.

HEARTH Act exceptions on reservations include fee simple land (private property), “fractionated” interests and individual Indian allotments of trust land, according to a webinar put on by the NMTHC and moderated by Dave Castillo, executive director of Native Community Capital.

Otherwise, the law allows tribes to approve and enforce leases on tribal trust or restricted land without a lease review by the Bureau of Indian Affairs or an approval by the Secretary of the Interior. In a related but separate development, tribes are increasingly running their own land title offices as well, removing yet another roadblock.

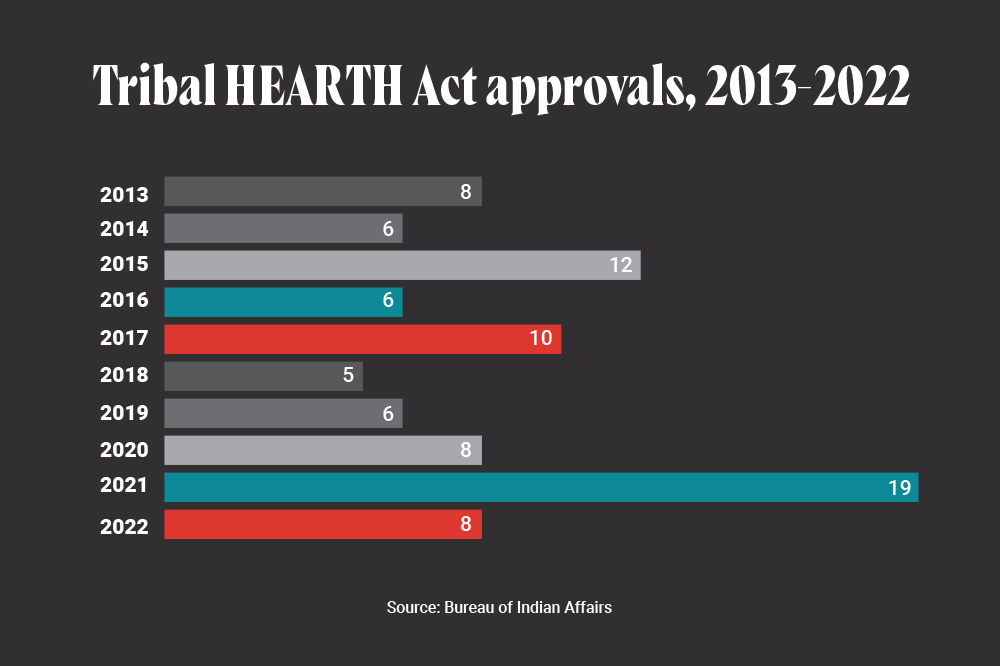

Lease approvals “can be a lengthy process,” so having the tribe handle it itself can shorten the time involved, said Sharon Kidman, a HEARTH Act Realty Specialist for the BIA who introduced a recent NMTHC panel on the topic.

Importantly, the process “refers to leasehold mortgages but not mortgages of tribal land,” Kidman said.

Having a leasehold mortgage gives lenders confidence they can attach the asset in case of a default. However, the mortgage is on the lease, and not the land. The usual effect is that a lender can attach the improvements (the house) but not the land beneath it.

Lease terms vary, but residential leases are for a maximum of 75 years, “although they can be less than that,” Kidman said. The HEARTH Act bans exploration, development or extraction from the land.

Having a speedier process is beneficial for tribal economic development, but tribes need to assess the added resources it will take for them to administer the program, she added. As well, existing leases completed under the BIA leasing authority can be renewed under the new HEARTH Act authority when they expire, Kidman said.

Sheila Herrera, executive director of Tiwa Lending Services, a Native community development financial institution (CDFI) based on the Pueblo of Isleta south of Albuquerque that lends to Isleta residents, discussed a couple of HEARTH Act-related challenges the community encountered.

Key questions include: “Is my tribe ready to enact leasing regulations? … How long does it take BIA to approve your leases? How long does it take your tribe to prepare leases under the HEARTH Act? And who is going to prepare your environmental reviews?”

Another one to ask, according to Herrera: “Are you prepared to manage, enforce or cancel leases?”

New hiring is another consideration: “Does the tribe have the capacity to process, approve and encode leases for recording?”

Herrera’s tribe is currently in the process of hiring a realty specialist to run the program. This may involve $77,100 in annual costs, including a salary of $52,000 and $10,740 for supplies.

“We don’t have a realty specialist,” she said. “We are trying to put it in our budget.”

Currently, the tribe “is just trying to overcome all these challenges,” according to Herrera.

Estevan Sando, operations manager at the Pueblo of Jemez Housing Authority said his pueblo, located about an hour north of Albuquerque, became a self governance tribe in 2013 and has established codes for both business and residential leases. The tribe applied to the BIA for HEARTH Act residential and business lease status in March of 2021 and got approved by the agency six months later.

“Being a HEARTH Act tribe is the only way to get recorded in a timely manner,” he said.

One thing that stimulated the tribe’s HEARTH Act application was Jemez started a solar project that required a business lease, Sando said.

“That got the tribe thinking of the HEARTH Act,” he said.

The tribe used the six months their application was pending to think about how it wanted to implement the process. Offices involved in the process included the tribal realty department, the natural resources department, and the Pueblo of Jemez Housing Authority.

“Becoming a HEARTH Act tribe has allowed us to expedite the residential leasing process for members who were seeking homeownership through various government loans, such as the HUD Section 184, the Native American Direct Loans through the VA, and USDA Section 502,” Sando said, noting that a pilot program for New Mexico pueblos to become HEARTH Act tribes would be a good idea.

Best practices at Jemez include the persistence of the tribe in pursuing the application and the efforts of the tribal departments involved, buy-in from the tribal council, and a federal review of the Jemez lease documents, he said. Challenges included the tribe’s lack of knowledge when it started the process, the interruption of the pandemic, and the process of identifying the key personnel at federal agencies.

“We were still smoothing these things out as we were going forward,” Sando said.