- Details

- By Chez Oxendine

- Policy and Law

Native leaders called on Congress last week to support land consolidation efforts in Indian Country during a hearing held by the House Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs.

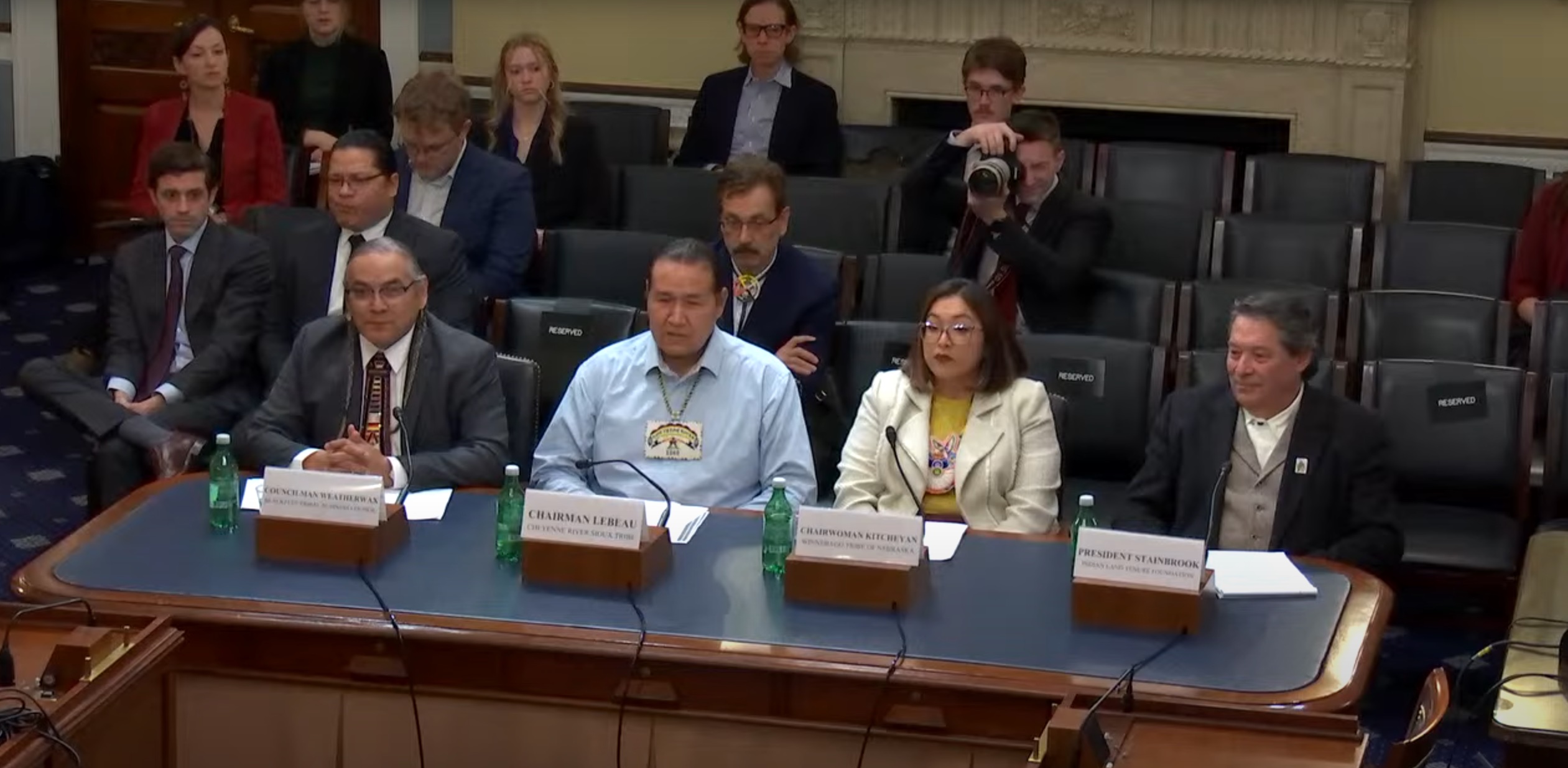

Speakers at the hearing included Blackfeet Tribal Business Council Member Marvin Weatherwax, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Chairman Ryman LeBeau, Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska Chairwoman Victoria Kitcheyan, and Indian Land Tenure Foundation (ILTF) President Cris Stainbrook. Darryl LaCounte, director for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, was scheduled to appear at the hearing, but could not attend due to illness.

Of central concern was the Land Buy Back Program, a 2012 initiative that allotted $1.69 billion and programmatic support for returning tribal lands through acquisitions and land into trust maneuvers. That program concluded in November 2022, leaving a gap in support for landback efforts and regulations that stifled attempts made with funding that was allocated. The Land Buy Back Program was succeeded by the Indian Land Consolidation Program in 2023, but funding for that program has fallen far short of its predecessor, with roughly $8 million in funding in 2023 per LeBeau’s testimony.

The prevailing refrain among the Native speakers centered on more funding and resources for consolidating lands under tribal control. Money was needed to buy private land that could create more contiguous tribal reservation boundaries and avoid fractionation, which continues to make acquiring those lands, and eventually taking them into trust, more and more difficult, per Weatherwax.

By 2012, when the Land Buy-Back Program was established, the Blackfeet Tribe had lost 90 percent of its original reservation and had the third-highest amount of fractionated land in the United States, making use and management of these lands difficult at best and “in many cases impossible,” Weatherwax testified.

Weatherwax contended that, even beyond fractionation, uses of the Land Buy Back Program funds were too narrowly defined. Short of additional funding, Weatherwax recommended allowing allocated funds to be used toward supporting tribal land departments, and toward other categories of land that did not fall under the fractionated categorization.

“My Blackfeet Tribe views the program as an important tool to restore Blackfeet ownership of reservation lands,” Weatherwax said. “We believe removal of bureaucratic impediments is central to achieving the goals of the Land Buy Back Program.”

While Weatherwax’s recommendations discussed solutions that didn’t necessarily require additional funding, LeBeau’s testimony centered on the need for it. LeBeau recommended approving the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ request for a $22.5 million increase to annual Indian Land Consolidation Program funding, as well as adding $400 million for purchasing fee lands that could be used to stimulate ailing economic development on the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe’s reservation.

More land, LeBeau said, could be used toward agricultural and economic development, assuaging an employment rate that, in Montana winters, skyrocketed to 85 percent.

“The Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe needs the value added agriculture that Buffalo production and other livestock production represents because we need jobs for our Lakota people to make our Cheyenne River Reservation a livable home,” LeBeau said. “Through land consolidation purchases, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe must recover reservation fee lands for value-added agriculture to feed and employ our Lakota people and Congress should help us.”

The Winnebago Tribe’s Kitcheyan echoed the sentiment, pointing to the subsequent success of its farming operation once more land was under direct tribal control, as well as the economic benefits for tribal members who received purchase offers for land consolidation. Ho-Chunk Farms Inc. has provided funding and economic support for further landback efforts, which in turn have supported more development.

The Land Buy Back Program’s success created a feedback loop that has boosted the tribe’s limited resources for land purchases and management - but still, more funding would help keep that process going, Kitcheyan said, and avoid fractionation that could quickly rise to pre-Program levels.

“The Department of the Interior has indicated that it would likely take billions of dollars to resolve the fractionation problem,” Kitcheyan said. “Increasing federal funding to help address the fractionation problem would greatly advance the Winnebago Tribe’s efforts to continue to consolidate our land base, increase economic self-sufficiency, and strengthen our community.”

Another track for possible funding was a bid to support land owners in improving their wills, said Stainbrook, whose organization, the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, specializes in consolidating estates fractured by years of generational division.

ILTF'S Stainbrook pointed to a pilot project launched in 2005 under the Department of Interior called the Estate Planning Services Pilot Project. The project had two purposes: educating Natives on the American Indian Probate Reform Act of 2004, which sought to improve the way allotment lands were handed down between generations, and improving estate planning services to avoid further fractionation.

Over the Estate Planning Services Pilot Project’s eight month tenure, just under 1,350 wills and 3,500 other estate documents were written - 84 percent of which resulted in consolidation, Stainbrook said in his testimony. Project costs of around $486,000 saved the Department of Interior roughly $3.75 million in future administration costs, Stainbrook also noted.

More funding for programs like the Estate Planning Services Pilot Project - and more funding for land purchases - could serve as chief ways to reduce fractionation, Stainbrook said. Other steps, such as simplifying and encouraging the use of gift deeds and legalizing the use of transfer on death deeds on trust lands, could also help.

“ILTF would recommend that Congress and DOI consider approaching the issue from multiple approaches to have any hope of correcting what your predecessors created more than 100 years ago,” Stainbrook said. “Now would be the time to take action and benefit from the reduction of undivided interest from the Land Buy-Back Program as it will only grow from here.”

Subcommittee Chair Harriet Hageman (R-Wyoming) thanked the hearing participants for their time and for “bringing solutions to the table.”

“We don’t always see that. Our witnesses don’t always come in with a list of things that they think need to be done to address the issue that is creating the problem at hand,” Hagerman said. “I appreciate that…bringing this list to us allows us to better focus on what is actually going to be a solution.”